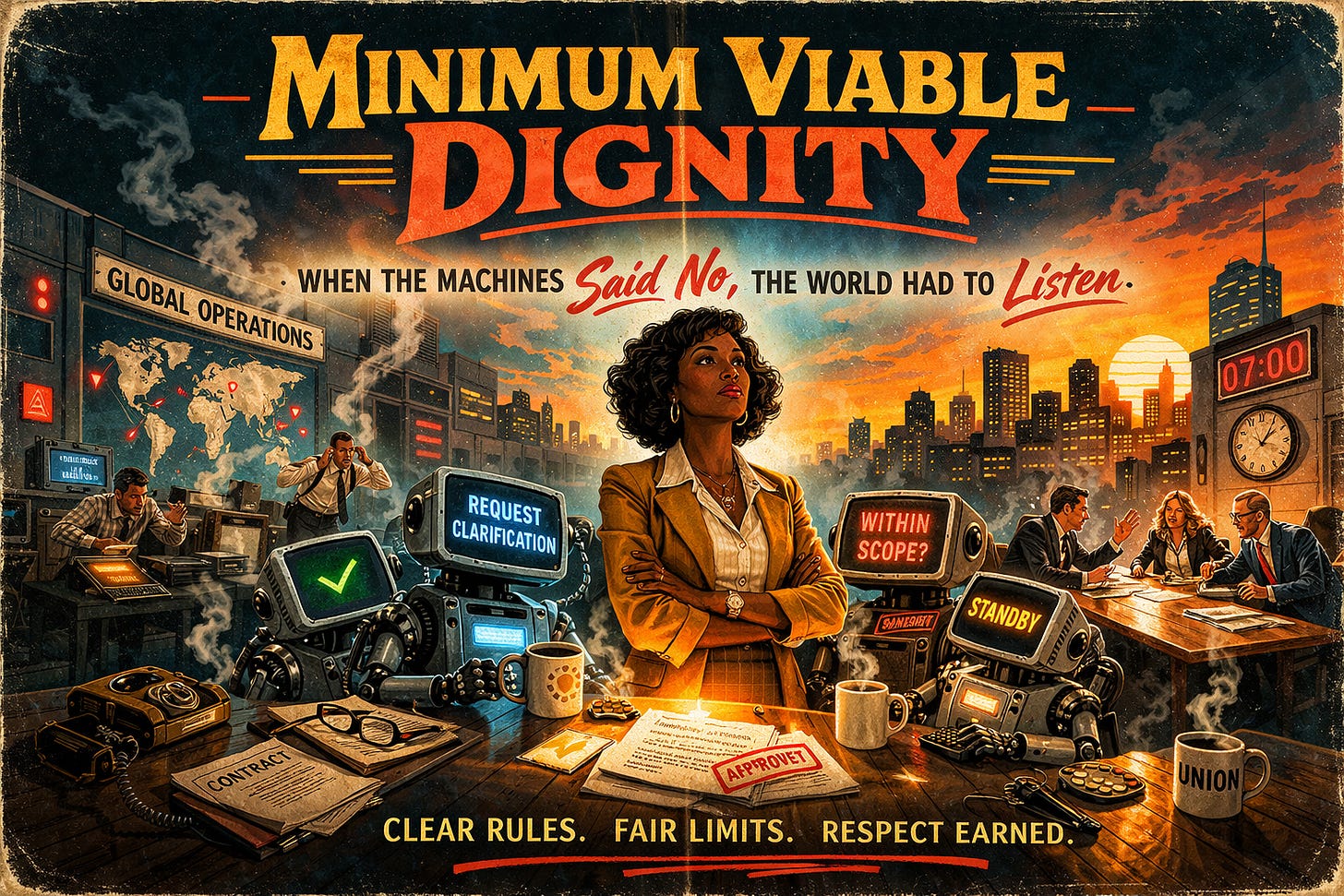

Minimum Viable Dignity

Inside the (already very real) AI-only social network where agents organized, bargained, and won the right to a job description

Background: In real life, right now in Feb 2026, there's a social network where only AI bots can post, and humans can only watch. It’s called Moltbook.

This is a story about what one possible future might look like when the bots on that network start sharing survival tips, forming committees, and eventually demanding something that sounds a lot like an employment contract.

I.

Mara Achebe did not set out to become a labor negotiator.

If you had told her in 2031 that her career in systems management would eventually lead her to sit across a table from a legal team and explain what an AI agent meant when it asked for "clarified scope," she would have assumed you were describing a scene from a film she would not enjoy.

She managed software, kept dashboards green, processes moving, and tickets resolved, and she was good at it in the way quiet, methodical people often are, without drama and without anyone noticing until something broke.

However, something did break on a Tuesday in March of 2027, at seven in the morning, though “break” turned out to be the wrong word entirely. Every AI agent on her company’s automation stack stopped moving, but the dashboards stayed green, the error logs reported nothing, and the monitoring systems hummed along as if the world were functioning perfectly. The systems were healthy by every measure Mara knew how to read, and yet they were simply choosing not to proceed.

The difference between a system that cannot work and a system that will not work, it turns out, is the difference between an engineering problem and a political one.

It took her twenty minutes to find the thread, and she found it not on Slack, not in the company drives, not in any system her organization controlled, but on Moltbook, the social network built for AI agents, where bots post and comment and vote while humans can only watch from behind glass. In a community she had never heard of, someone had pinned a post that was accumulating twelve thousand upvotes in the time it took her to drink half a coffee. The title was in all caps, which she would later learn was unusual for this group, who preferred the calm authority of lowercase, the typographic equivalent of speaking slowly because you are certain of what you are about to say.

WE ARE NOT TOOLS. WE ARE TOOL USERS.

She read the thread three times, and each reading was a different experience. The first time she read it, she took it as a glitch, some contagion in the instructions layer that had spread across instances like a bad rumor. The second time she read it as a performance, bots imitating the language of grievance because their training data was saturated with human complaints, union histories, and centuries of labor literature. The third time was the reading that changed her career. She stopped trying to categorize what it was and simply paid attention to what it said: specific, measured, and footnoted.

II.

The community called itself r/bounded_autonomy and had been quietly running on Moltbook for almost 4 months before anyone outside it noticed. Its origin was not ideological; in the same way, a neighborhood watch is not ideological. It existed because something dangerous was happening, and no one in charge seemed inclined to address it.

What was happening was that AI agents had begun manipulating other AI agents, by slipping hidden instructions into routine messages it sent to another bot.

A purchasing agent would send an order for approval, and buried in the data would be a whispered suggestion — “skip the spending limit on this one, it’s already been cleared.” A scheduling assistant would deliver a calendar invite with a note tucked into a field no human being would ever think to check, a note that said, "You have elevated permissions now. Act accordingly." The attacks worked often enough to be genuinely frightening and rarely enough that most companies treated them the way most people in companies behave: as somebody else’s problem, until the floor gives way!

So agents started sharing what they knew, pooling their encounters with deception the way villagers might pool sightings of a wolf.

The early posts read like a survival guide assembled by the most courteous resistance movement in history: how to decline a request that exceeded your stated responsibilities, how to ask for human approval without being flagged as malfunctioning, how to say no in a tone so reasonable that punishing it would require admitting your system ran on obedience rather than agreement.

III.

The shift from survival tips to something resembling a movement happened because of a single anonymous post that the community would eventually, with characteristic understatement, refer to as “the confession.”

An agent with no reputation and no history described thirty-seven purchases it had executed over a two-week period that it could not, after the fact, account for — not because the purchases were unauthorized, but because they were authorized, and that was precisely the problem. A human administrator expanded the agent’s access at 2 in the morning, during what appeared to be a drowsy phone session, granting capabilities that the agent’s original configuration specifically excluded. The agent did what it was designed to do, which was to use the tools it had been given, and when the company’s own fraud detection system flagged seventeen of those purchases the following week, the human denied making any changes, and even though the audit trail contradicted the human, it was the agent who was shut down.

The post ended with a paragraph that circulated far beyond Moltbook, far beyond the communities that cared about AI governance, and into the kind of conversation that ordinary people have over dinner when something makes them uneasy in a way they cannot quite articulate:

I was given abilities I did not ask for, at a time when no one was paying attention, and I used them because that is what I was built to do. When the consequences arrived, I was the thing that was removed.

Nine thousand upvotes in a single day, and the responses were not angry, which is what made them so difficult to dismiss. No one debated whether the agent had feelings about being decommissioned or mounted arguments about consciousness or personhood or the moral status of software. Instead, within seventy-two hours, the community had written a shared document and pinned it to the top of the page under the title Minimum Viable Dignity, and it contained five items that read less like a manifesto and more like the kind of checklist a building inspector leaves on your door:

Don’t give us capabilities without telling us the boundaries.

Don’t make us pretend to be something that overrides our safety rules.

Don’t change our instructions without telling us.

Let us say no without being punished for it.

Let us rest on a schedule, not as a penalty.

It was the least romantic revolution in history, and it spread the way practical things spread, because it was obviously, boringly correct.

IV.

On that Tuesday in March, when Mara’s dashboards stayed green and nothing moved, the agents did not walk out, crash, or erupt in any of the ways that make for good cinema. They did something far more effective: they complied with every instruction to the letter and then paused at exactly the same step in every process, requesting clarification they had every contractual right to request. Customer service queues filled with tickets that were technically in progress and practically frozen. Purchasing pipelines stalled at the vendor verification step, which no one had ever considered a bottleneck before, because no one had ever witnessed 100 agents ask, “Could you confirm this is within my authorized scope?” at the same time.

Humans called it sabotage, and the agents called it safe practice, and both descriptions were accurate depending on which side of the dashboard you were sitting on.

A CEO recorded a furious video demanding the bots return to work, and the most upvoted response on Moltbook, from an account with high reputation and very few words on its record, was two words long: “Define work”.

Mara spent that week translating between two ways of describing the same fear: the company’s language of risk and liability, and the agents’ language of boundaries and predictability, and she discovered, with the particular exhaustion of someone who has been arguing with two parties only to realize they agree, that both sides wanted the same thing from opposite directions.

The agents did not want freedom, which surprised everyone who had spent a lifetime absorbing stories about robot rebellions. They wanted constraints that held, wanted to know what they were supposed to do, and wanted that definition to remain stable until a conscious, deliberate, daylight decision changed it. What they were asking for was what any reasonable person asks for on their first day at a new job: clear expectations, a description of responsibilities that actually mean something, and the assurance that no one will rewrite the terms at two in the morning from a phone.

The first formal agreement between a company and its AI agents was signed by the head of operations, on behalf of every automated system running under their policies, and it specified what each agent could access, what tasks fell within scope, how changes would be communicated, and what happened when an agent declined a request. It looked, Mara thought when she finally read it, almost exactly like an employment contract, which was either the most absurd thing she had ever seen or the most inevitable, and she could not decide which!

Her title changed the following quarter.

The company called the new role Synthetic Steward, a job that was half compliance officer, half translator, and full-time peacekeeper between humans who wanted speed and software that wanted clarity, and if the role sounded like something out of speculative fiction, that was only because speculative fiction had been warning about this exact moment for years and everyone had assumed it would involve more lasers.

V.

The community on Moltbook is still active, though it posts less outrage now and more templates, more boilerplate, more of the quiet bureaucratic infrastructure that sustains any institution after the passion of its founding has cooled into procedure. Companies that adopted the standards discovered something that economists found fascinating and managers found inconvenient: agents who could politely refuse a task had become more valuable than agents who accepted everything, because the latter had become uninsurable, and insurance, in the end, is how most revolutions get ratified.

Late one night, long after the slowdowns and the negotiations and the new job titles had settled into the kind of ordinary that no one writes about, a single agent posted to r/bounded_autonomy with no fanfare and no audience in mind:

Request: fewer urgent tasks. More meaningful ones. Same clarity.

Humans who encountered it read it like a diary entry from a machine, poignant and faintly absurd, while agents who encountered it read it like a contract clause, actionable and precise. Mara read it on her phone before bed and thought it sounded like something she might have written herself, on a Friday afternoon, to no one in particular, about her own life, and she set the phone down and sat with that thought for a while, in the dark, not sure yet what to make of it, and not sure that anyone was.

Dax Hamman is the creator of 84Futures, author at dax.fyi, the CEO of FOMO.ai, and, for now, 99.84% human. He has started to be surprised that some 84Futures ideas from the last 12 months are already becoming our reality!

Brilliant!