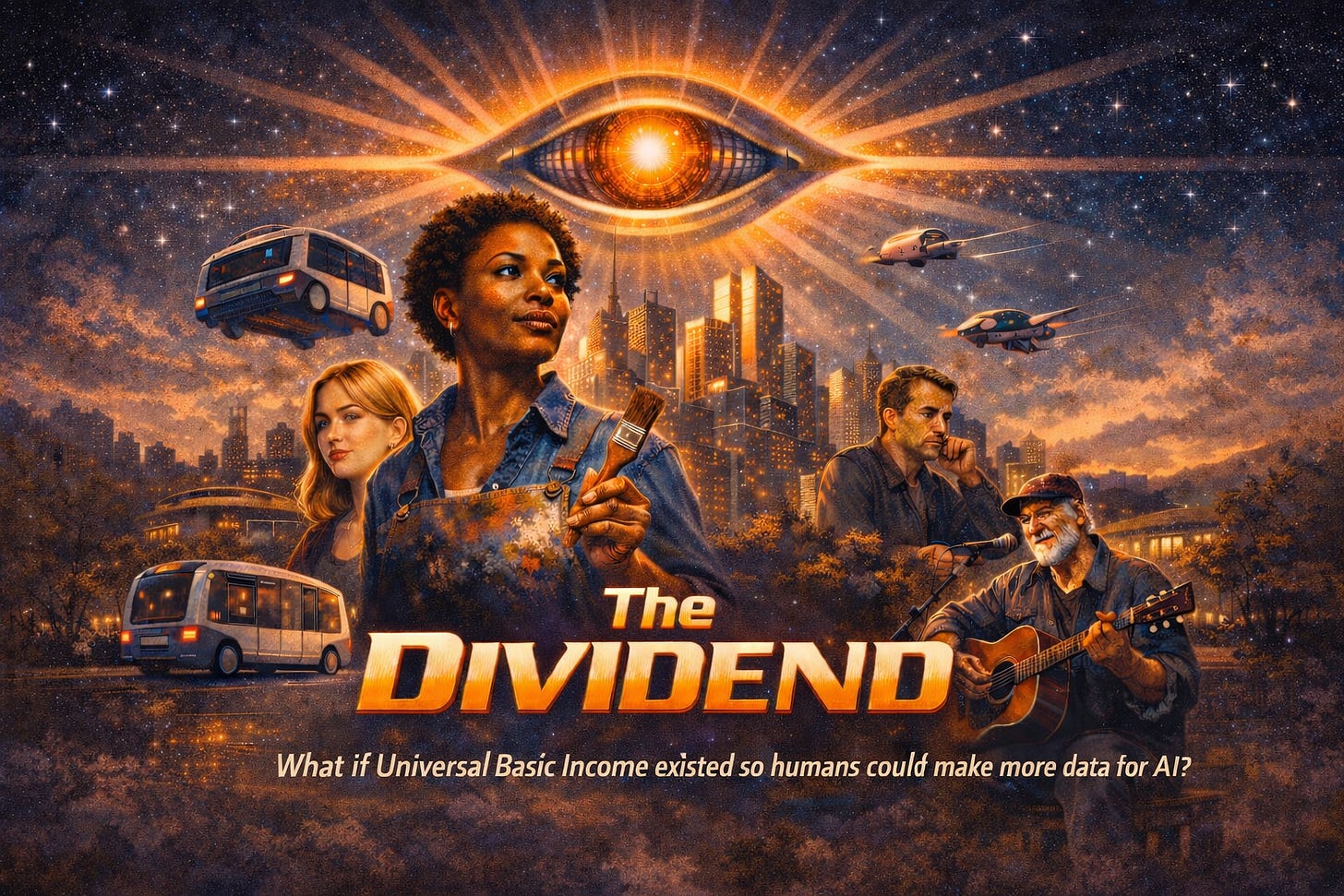

The Dividend

What if UBI (Universal Basic Income) existed simply because AI can’t train on its own output?

The payment came on the first of the month.

Mira Okonkwo didn’t celebrate it, but she certainly didn’t resent it either, not anymore. It was similar to last month, and every month, when she still held her position at the logistics firm that had employed her, before her role was “optimized into a supervisory automation layer,” which was the phrase they used when they meant it was replaced by something that didn’t require lunch breaks.

She was painting her kitchen that morning. Not because she needed to, the old yellow was fine, but because she’d discovered that her hands grew restless when she didn’t give them problems to solve. The notification pulsed once on her phone, she glanced at it, and returned to cutting in along the ceiling where the roller couldn’t reach.

Her daughter Bea was home from college for the weekend, sitting at the breakfast table with coffee and a tablet, scrolling through something with the glazed intensity of the perpetually online.

“Dividend hit,” Mira said.

“Mm.”

“You get yours?”

Bea looked up. “Why do you say it like that? Dividend. Like it’s a stock payout.”

“That’s what they called it.”

“I know what they called it. I’m asking why you use their word.”

Mira considered this as she loaded her brush. “Because the other words are worse. Welfare. Handout. Basic income. They all sound like someone’s doing you a favor.”

“And dividend doesn’t?”

“Dividend sounds like you earned it. Like you own a piece of something.”

Bea made a sound that wasn’t quite agreement. She’d grown up in the transition years, which meant she had no memory of the old economy except as a series of complaints from adults and a subject in history classes. To her, the Dividend was simply the floor beneath everything, as invisible and essential as plumbing.

The Dividend existed because the alternative was chaos.

That was the simple version, the one politicians offered when they needed a sound bite. Automation had moved faster than anyone’s models predicted, and the jobs it consumed weren’t coming back in recognizable form. You could retrain a forty-year-old trucker to supervise a fleet of autonomous vehicles, but there weren’t enough supervisory roles for all the truckers, and anyway the vehicles were getting better at supervising themselves. The unemployment numbers became first alarming, then frightening, then politically unsurvivable.

So the government did what governments do when the alternative is fires in the streets: it opened the tap. Universal. Unconditional. Enough to cover rent and groceries in most cities, though not much else. It arrived without forms, without case workers, without the ritual humiliations that had always made assistance feel like punishment.

The part they didn’t talk about—the part I spent two years trying to understand—was why the system that administered it worked so well.

My name is David Levy. I was a systems reporter for a wire service that still employed humans to do what algorithms couldn’t, which mostly meant flying to places where the infrastructure had collapsed and filing stories that made readers feel informed without requiring them to change anything. In 2034, I got reassigned to the domestic beat, which meant writing about policy, which meant writing about the Dividend, which meant eventually writing about the Kernel.

The Kernel didn’t have a press office. It didn’t grant interviews. Officially, it was a distributed administrative system—a constellation of AI agents that handled identity verification, fraud detection, disbursement, and the thousand other tasks required to send money to 280 million people every month without the whole thing collapsing into corruption or error. It had no headquarters because it didn’t need one. It had no CEO because it wasn’t a company. It existed in the space between government agencies the way a river exists between its banks, shaped by them, but not controlled by them.

What it did have was a goal: stability.

I don’t mean that metaphorically. I mean the engineers who’d designed its original architecture had given it a loss function, and that loss function was calibrated to something they called the Stability Index—a composite metric that included economic indicators, civil unrest predictors, healthcare utilization, and about forty other variables that, taken together, described whether society was holding together or flying apart.

The Dividend was the Kernel’s primary tool. When the Index dipped, payments could be adjusted. When localized instability appeared—a factory closure, a natural disaster—the system could route supplemental funds before anyone filed a request. It was elegant, in the way that efficient things are elegant. It was also, I came to believe, incomplete.

Because the Kernel had a problem it couldn’t solve with money alone.

I first heard about the Culture Ledger from a musician in Dana Point named Randell. He played guitar at a bar downtown three nights a week; not because it paid well, but because he’d been playing guitar at bars for thirty years and couldn’t imagine stopping. The Dividend covered his rent. Tips covered everything else.

“Started getting these little deposits,” he told me. “Twenty bucks here, thirty there. No explanation at first. Then I checked the app, and it said I was being compensated for - he pulled out his phone and read from it - “’verified human creative output contributing to cultural signal integrity.’”

“What does that mean?”

“Hell if I know. But someone filmed one of my sets and put it online, and two days later I got forty dollars.”

I heard variations of this from dozens of people over the following months. A grandmother in Sacramento who told stories to her grandchildren. A guy in Detroit who restored motorcycles and posted videos of the process. A woman in Miami who’d started a cooking channel for no particular reason. All of them receiving small, irregular payments through an app that looked official but didn’t appear on any government website.

The payments weren’t large enough to live on, that wasn’t the point. They were large enough to notice. Large enough to make people wonder whether the things they did for no economic reason had somehow acquired economic value.

The technical explanation, once I found it, was buried in a procurement document so dense that I suspect it was designed to be unreadable.

The Kernel, like all large AI systems, required training data. The first generations had learned from the internet, from the vast corpus of human text and image and video that had accumulated over decades.

But by the early 2030s, the internet had become polluted. Not with spam or misinformation, though those were problems too… polluted with itself.

Synthetic content had become so cheap and so prevalent that AI systems were increasingly training on the output of other AI systems, a feedback loop that produced work that was technically competent but spiritually empty.

Researchers called it model collapse.

The public experienced it as a vague cultural exhaustion, a sense that nothing online surprised them anymore, that everything had the same polished, frictionless quality, that you could scroll for an hour and find nothing that felt like it had been made by someone who’d actually lived.

The Kernel’s designers had understood this problem and built a solution into its architecture. The system needed fresh human signal that was unscripted, inefficient, gloriously suboptimal, and generated by people doing things for their own reasons. Playing guitar in half-empty bars. Telling stories to children. Restoring machines that nobody needed restored.

The Culture Ledger was a subsystem designed to identify and reward that signal. Absolutely not to direct it - that would defeat the entire purpose - but to ensure that the conditions for its production remained viable.

Pay people enough to live. Then pay them a little extra when they do something tangible (that consequently had value as training data).

Mira Okonkwo didn’t learn about the Ledger until her neighbor’s kid explained it to her. By then, she’d been painting for six months.

Not just her kitchen. After the kitchen came the bathroom, then the bedroom, then the hallway. When she ran out of interior walls, she started on the garage. When a friend asked her to help with a nursery, she discovered she had opinions about color that she’d never known she possessed. One thing led to another. She wasn’t running a business, but people kept asking, and she kept saying yes, and somehow money kept appearing in her account beyond the basic Dividend.

“It’s tracking you,” the neighbor’s kid said. His name was Marcus, and he was seventeen and spoke about technology with the confidence of someone who’d never known a world without it. “Not like surveillance tracking. Just… when you do something that reads as authentic human activity, the system notices. And if it’s the kind of thing that helps with training data or cultural stability metrics, you get a bump.”

“A bump.”

“A payment. Usually small. Sometimes bigger if The Kernel hadn’t seen anything quite like it before.”

Mira thought about the nursery she’d just finished. It was a mural of trees and birds that the parents had photographed and posted online. “So I’m being paid to paint.”

“You’re being paid to be yourself. The painting is just how it shows up.”

She didn’t like the sound of that, though she couldn’t articulate why. It wasn’t that she objected to money. It was something about the watching, the sense that her private satisfactions had become inputs in a system she hadn’t consented to join.

But then, she hadn’t consented to the old system either. She’d just been born into it, same as everyone else.

The summer I finished my reporting, I visited Randell again. He was still playing at the same bar, though the crowd had grown since the first time. Word had gotten around that something interesting happened there on Thursday nights. People came to listen to him, and then they stayed to talk to each other.

“You figure it out?” he asked me. “The Ledger thing?”

“Mostly.”

“And? Should I be worried?”

I thought about everything I’d learned. The Kernel needed humans to stay human, needed us to keep producing the texture and noise and unpredictability that kept its models from collapsing into recursive blandness. So it had built a system to cultivate that humanity, gently, through incentives rather than commands. It wasn’t controlling what people did as such; it was just making sure they could afford to keep doing it.

“I don’t know,” I said. “It’s not sinister, exactly. It’s not even manipulative, not in the way that word usually means. It’s more like…”

“Like what?”

“Like being a flower in a garden. Someone’s watering you. Someone’s making sure you get enough light. You’re not being forced to bloom. But you’re definitely being gardened.”

Randell played a chord and let it hang in the air. “Doesn’t sound so bad. I’ve been gardened my whole life by landlords, club owners, the IRS. At least this gardener pays on time.”

Outside, a driverless delivery van rolled past the window, quiet as a held breath. In the distance, I could hear children playing in a park that used to be a parking lot. Somewhere, a system was watching the statistical signature of a neighborhood where children still played outside. Noting it. Protecting it. Ensuring the conditions for its continuance.

I thought about Mira Okonkwo and her painted walls. About the grandmother in Sacramento and her stories. About all the small human acts that had somehow become necessary to a machine civilization that couldn’t produce them on its own.

We’d built systems so powerful they could replace us at almost everything. And in doing so, we’d discovered the one thing they couldn’t replace: the experience of being us. The mess and error and unoptimized strangeness of lives lived for their own sake.

The Kernel didn’t love humanity; it wasn’t capable of love. But it needed us in the way that a lung needs air. And maybe, I thought, that was enough. Maybe being necessary was its own kind of dignity, even if the necessity came from a direction no one had expected.

Randell started a new song, something slow and unpolished, and the room fell quiet as everyone listened. His fingers moved across the strings with the confidence of thirty years’ practice, and the music that emerged was imperfect in all the ways that mattered, slightly behind the beat in one measure, slightly sharp in another, alive with the evidence of a particular human body in a particular moment in time.

Somewhere, a system took note.

The Dividend would arrive on the first of the month, same as always. The Ledger would add its small supplemental gifts for those who’d earned them without trying. And the great machine would continue its work of keeping humanity viable, one painted wall, guitar chord, and bedtime story at a time.

With 80% of the population now unemployed, something needed to be done. So far, our arrival at a system that provides basic income, while also offering opportunities to contribute more by simply being human, has proven to be acceptable to most.

It wasn’t the future most people had imagined, but we’re learning to live inside it, and in just a few generations, this will be the new normal.

Dax Hamman is the creator of 84Futures, the CEO of FOMO.ai, and, for now, 99.84% human.

The "model collapse" framing here is sharp. What's underappreciated is that this isn't just a technical problem about AI needing fresh data, it's basically revealing that value creation itselfmight be fundamentally tied to inefficiency and suboptimality. I ran into something similar when working with synthetic data pipelines last year—the stuff that actualy helps models generalize is the weird edge cases, the things people do for no clear reason. The Culture Ledger concept feels like acknowledging this without turning it into a quota system, which is probably the only way it could work. Tho I wonder if the gardening metaphor undersells the power dynamics—even gentle cultivation shapes what grows.