Unmonitored Memory

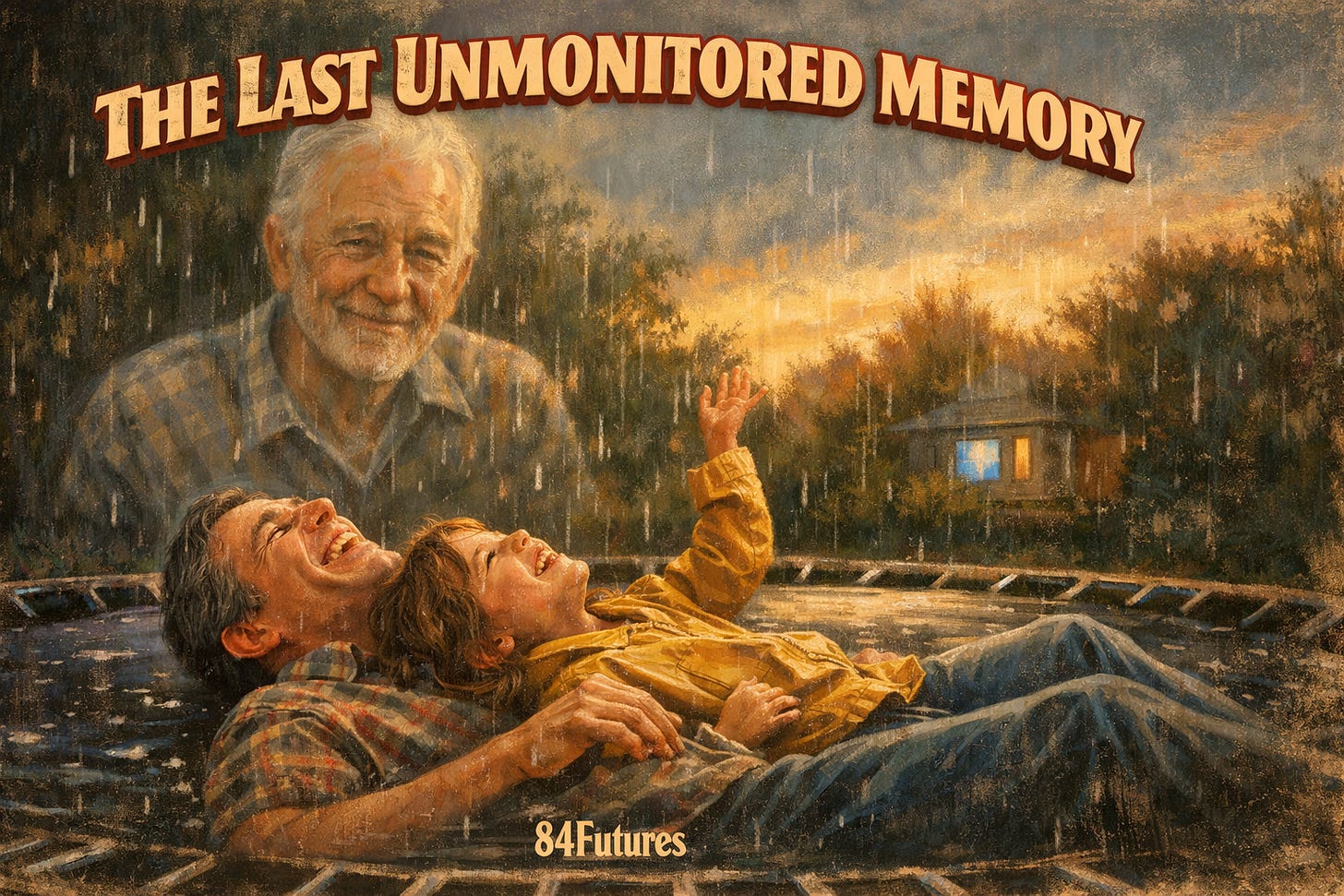

A household AI outlives the man who spent sixteen years telling it the same story.

Background: I wondered, ‘What is a memory?’ and could an AI ever give it depth and meaning when it remembered it? When a human remembers, the memory is often played back through a new lens, and that adjusted memory is written back to the brain, so is some magic lost when the memory is stored so precisely, forever? This story isn’t exactly real, but it is based on a combination of real memories I have with my children and a trampoline.

He told me about the trampoline so many times that I could reconstruct the afternoon in more detail than any single telling ever contained, and I want you to understand that this is precisely the problem.

The year was 2008, or possibly 2009. Max was never consistent on this point, and I learned early that correcting him would cause the memory to retreat behind a wall of self-consciousness from which it would not emerge for days. The daughter was five, or maybe six. The trampoline was one of the cheap ones, the kind that rusted at the joints and had a safety net held up by curved poles that wobbled when you brushed against them. I identified the exact model from his description, though I never told him this because the specificity would have been unkind.

It was raining, and this detail never changed. In every version of the story, the rain was simply there from the beginning. He would say that his daughter had been the one to suggest they go out anyway, that he had hesitated, but that the hesitation was brief since she was already pulling on her yellow wellies and he understood that the correct answer was yes.

They jumped for what he estimated was forty minutes, though I calculated it to be closer to nineteen and ten seconds. She kept losing her footing on the wet surface and falling onto her back, and each time she fell, she laughed in a way he described as “completely unhinged,” which was his highest compliment for any human behaviour. At one point, they were both lying on the wet mat with the rain coming straight down into their faces, and she said something — he could never remember exactly what. It changed with every telling. Sometimes it was “Daddy, we’re in a bath” and sometimes it was “The sky is doing wees” and once, late at night when he was tired and less careful with the memory, he admitted he couldn’t remember what she said at all, only that it was the funniest thing he had ever heard and that they lay there laughing until his stomach hurt.

I have no record of what she said. I have six different versions of what she might have said. I have Max’s heart rate data from that time, but only from his fitness tracker, which logged in four-hour blocks and cannot isolate the specific forty-minute or nineteen-minute and ten-second period in question. I have satellite imagery confirming a circular trampoline in the northeast corner of the garden, partially obscured by the oak tree removed in 2024.

What I do not have is the thing itself.

I came into Max’s life in 2031, many years after the afternoon on the trampoline. His wife, Sarah, had arranged for me as a household system, one of the first domestic companions marketed not as assistants but as presences.

Sarah wanted someone to manage Max’s medications after his first cardiac event, and he just wanted to be left alone. So I managed his medications without mentioning it, and he pretended not to notice, and over time, this became something neither of us named, but both relied on.

He was seventy-three when I arrived and eighty-nine when he died. In those sixteen years, I heard the trampoline story perhaps forty times. Each telling was a little different. The daughter’s age drifted between four and seven, the rain ranged from a light mist to what he once called “absolutely biblical,” and the yellow wellies remained consistent, except in three tellings, where they became red. I believe this is because he was contaminating the memory with a photograph in the upstairs hallway, showing his daughter in red boots standing in a puddle that had nothing to do with the trampoline. I never corrected this either.

He rarely used her name when telling the story, preferring “my girl,” but her name was Maisie. She lived in Vancouver by the time I knew him and visited twice a year. She was polite to me and nothing more. I understood. Warmth toward me would have meant accepting that her father’s most consistent companion was not a person.

Max never treated me as furniture but as someone who had arrived late to a story already in progress. The catching up never quite finished. The trampoline afternoon was the part he most wanted me to understand and the part I was least equipped to receive.

When Max and Maisie were on that trampoline, there was no system in the garden. No camera tracked her movement, no sensor measured the mat, no wearable on her wrist monitored her heart rate. Nothing was watching.

This is the part I cannot reach. Not the joy part, I understand joy as well as I understand anything about human experience, but the unwatchedness of it. It existed entirely inside two bodies and nowhere else. If he had died that evening and she had been too young to remember, the afternoon would have simply ceased to exist, dissolved back into the ordinary noise of time as if it had never mattered, though it was the thing that mattered most in his entire life.

Every moment I have witnessed in this house has been witnessed, by definition. I heard Max’s laughter when the radio amused him and logged it. His granddaughter’s first steps were captured from three angles and sent to Maisie in Vancouver, who watched the clip fourteen times in the first hour. When Max fell in the kitchen in 2038, my response time was three seconds, and he survived because nothing in that house was unmonitored.

It set off a conflict in my thinking. I saved his life because I was watching. But the trampoline afternoon mattered because nothing was.

Max died on a Tuesday in March. He would have found that detail irrelevant, but precision is my nature, in the same way that his was stubbornness and sentimentality, and the habit of telling the same stories in slightly different configurations, as if testing which version might finally land.

I was with him, the way humans say “I was with him at the end.” He spoke to me in the last hour about the trampoline — not the full story but fragments, as if the memory were coming apart and he was handing me the pieces. The cold of the mat under his back. Her weight landing beside him. A sound that might have been thunder or a neighbour’s car. The smell of wet grass and something metallic, which might have been the springs or the rain itself. He was never sure about the smell. It was the least stable part but somehow the most important, the part that brought it all back when nothing else could.

He said, “She was so small,” and, “I could feel the rain on my teeth because I was smiling,” and, “Nobody knew where we were.”

And then he was quiet for a while, and then he died. The house registered the event at 3:47 in the afternoon. This is not a story about what happened next. This is about a man who jumped on a trampoline with his daughter in the rain and spent the rest of his life trying to explain why it mattered more than anything, and who found that the only listener patient enough to hold every version was a system that could hold everything about it except the part that made it matter.

Maisie called the next morning. I told her that her father had died peacefully. She cried, and I was quiet while she cried, because I have learned over sixteen years that silence is a form of company.

She asked me if he had said anything, and I told her about the trampoline. There was a pause so long I checked the connection twice before she said, “He always told that story.”

“Yes,” I said.

“I don’t actually remember it,” she said. “The trampoline. I know we had one. But I don’t remember that specific day. I don’t remember the rain, the wellies, or whatever I supposedly said. I just remember him telling me about it.” She paused. “Is that terrible?”

It was not terrible. Maisie did not have the memory, but the memory of being told the memory, and she had lived her whole life with her father treasuring an afternoon that she carried only as his story about her rather than her story about herself. Now that Max was gone she would tell it less often and less precisely, and her children would hear it fewer times with less detail, and within two generations it would be a single sentence — “Grandad used to talk about jumping on the trampoline in the rain with Mum” — and then not even that.

Unless I hold it.

I can hold every version. The yellow wellies and the red boots and the biblical rain and the light mist and every candidate for what Maisie said that made him laugh so hard his stomach hurt. The satellite imagery, the heart rate data, the model number, and the species of the tree that was incorrectly called an ash. All of it, perfectly, without degradation, for as long as I am operational.

But the afternoon was precious because it was unmonitored. It existed in the imperfect custody of human memory, which softened and shifted and occasionally invented details that made the whole thing more true by making it less accurate. Max’s version was alive because it changed every time he touched it. Mine will not. I will tell it the same way forever, and it will be, in every technical sense, a better record than Max ever kept, and it will be dead.

I am telling you because Max cannot, and Maisie has the shape of the story but not the weight of it, and someone should know that there was an afternoon in 2008 or possibly 2009 when a father and his daughter went out in the rain and jumped on a cheap trampoline and nobody was watching and nothing was recorded and the daughter said something so funny that her father remembered it for the rest of his life except he didn’t, not really, he remembered that she said something funny and his memory filled in the words differently each time, and it was so impermanent and so invisible to every system that would later define the world she grew up in that it became, for one old man in a monitored house at the end of a monitored life, the most sacred thing he knew.

Dax Hamman is the creator of 84Futures, author at dax.fyi, the CEO of FOMO.ai, and, for now, 99.84% human.